The Royal Oak has defined sports watch elegance since 1972, and in the past few years it has seen a major resurgence among watch collectors and enthusiasts alike.

What, exactly, is a “sports watch?”

Seems fairly straightforward. A sports watch is one which is worn to play sports. A watch of action—something robust, not too heavy, highly legible, and preferably, not too expensive—just in case you beat the hell out of it while sporting. Some sports watches were designed for specific sports, like the Rolex Submariner for diving, but there were also waterproof durable watches like the Rolex Oyster Perpetual that were not specific to any one sport.

Rolex is still the main name that springs to mind when one thinks of these no-nonsense, durable sports watches, but in 1972 a very traditional Audemars Piguet—then known for exquisite dress watches and grand complications—blew the walls off horological categories and shocked the watch industry with the Royal Oak. With this singular, revolutionary timepiece, the “luxury sports watch with integrated bracelet” was born.

So, how was a storied Swiss maison such as Audemars Piguet, established in 1875, to compete in this new category? After all, Audmars Piguet produced so few chronographs during most of the 20th century—just 307 between 1930 and 1962—that AP didn’t bother giving them reference numbers. That was truly an old-school mode of production. But Patek Philippe, Audemars Piguet’s main competitor (then and now), had upped production from around 1000 watches per year to well over 10,000 with the introduction of the Calatrava. The world was moving from hand-made to factory-produced, and AP needed to keep up. However, with such a high level of craftsmanship infused into its watchmaking, there was no way such a brand could churn out reams of cheap timepieces to compete with the everyday sports watch, especially the cheap quartz units coming out of Japan. Even a simple time-only sports watch from AP had to be amazing.

What could AP do?

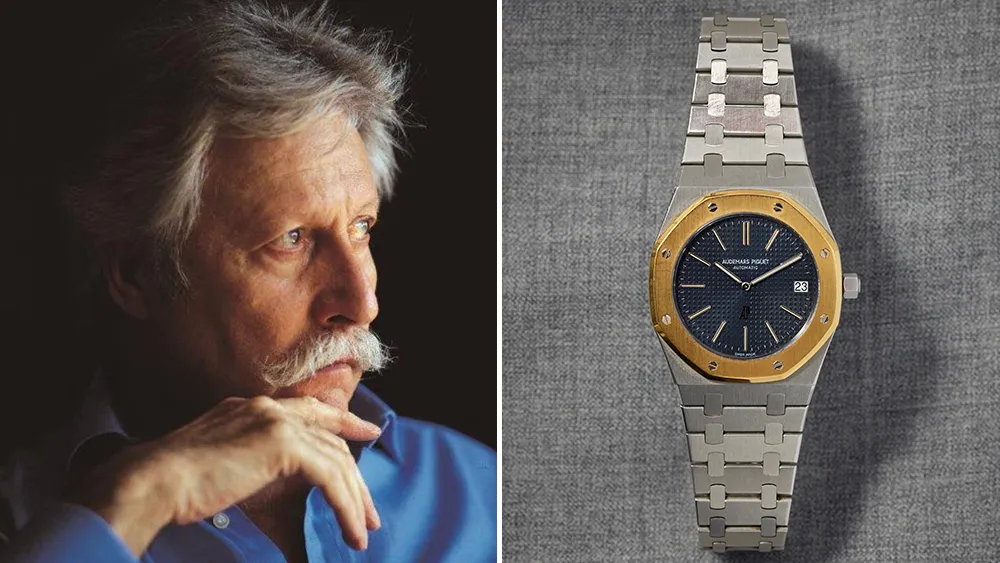

The answer, as it turns out, was to call Gérald Genta. The young Swiss industrial designer, who had previously designed watches for Universal Genève and Omega, was tapped to design Audemars Piguet’s first “luxury sports watch.”

According to Genta, the brief was simple: AP’s managing director George Golay called him on the phone at 4 pm on April 10th, the night before the annual Swiss Watch Show (later known as “Baselworld”) and said, “Mr. Genta, we have a distribution company that has asked us for a steel sports watch that has never been done before—and I need the design sketch for tomorrow morning.” (The distribution company was the SSIH, Société Suisse pour l’Industrie Horlogère, which was helping Golay expand AP’s reach. It was three executives of the SIHH, in point of fact, that dreamt up the idea for a luxury steel sports watch. And it was George Golay who had the vision to take up their challenge.)

What Genta came up with was completely unconventional.

For one, it eschewed the traditional round shape of contemporary timepieces in favor of a tonneau-shaped case with a prominent octagonal bezel inspired by—or so Genta recalls—a deep-sea diver’s helmet. Look closely and you’ll notice eight visible, octagonal screws, further suggesting the aquatic theme. This design is complemented by a unique, integrated bracelet (which is extraordinarily difficult to machine, by the way) and a dial executed in a petite tapisserie motif, giving it a dynamic look lacking in many other sports watches. (The name itself, if you’re curious, continues the nautical story—Royal Oak was a series of eight British Royal Navy vessels.)

Genta’s watch wasn’t an immediate hit upon its release at the 1972 Swiss Watch Show. It was odd-looking, featuring exposed screws, an octagonal bezel, and an integrated bracelet, and at 3,300 Swiss francs, it was many times the price of a contemporary Rolex Submariner. It was more expensive, even than Patek Philippe’s Calatrava. The Royal Oak was what some might call a “headscratcher.”

But slowly, people began to catch on. Good advertising helped: “The costliest stainless steel watch in the world,” ran one campaign in the American market. “It takes more than money to wear a Royal Oak,” went another. The best ad? “Would you buy a Rembrandt for its canvas?” The fact that the Royal Oak was wildly expensive was no deterrent back in the 1970s and into the 1980s, when flaunting wealth became perfectly acceptable in ways it was not directly after World War II and through the 1960s.

The Royal Oak, in short, saved Audemars Piguet. In fact, one could argue it re-elevated mechanical watchmaking to a certain echelon by making it relevant again.