Forty minutes’ drive from Beaune, in the unshowy village of Givry, sits a family domaine that owns 1.83 hectares of Montrachet Grand Cru – and yet many Burgundians, let alone collectors, have barely heard of it.

I first drove to Givry to visit Domaine Baron Thénard in late January 2020, with only a hazy sense that they owned vines in Montrachet Grand Cru. The village is roughly 30–40 kilometres – about forty minutes by car – south of Beaune, but psychologically it might as well be another region: fewer Teslas, more tractors.

I expected something modest; I did not expect to be led straight into a 17th‑century rock‑hewn cellar and handed a pipette over 18 barrels of Montrachet Grand Cru. The wine was not in 18 different barrels, but in small groups of each type – a couple of new Rousseau “Vidéo” casks here, a pair of older Cadus barrels there, a run of Chassin and François Frères – enough multiples to let you hear the same melody sung in different acoustic spaces. Tasting through those groups hammered home two things: the sheer physical scale of Thénard’s holdings, and just how profoundly barrel choice shapes the wine’s texture and aromatic profile.

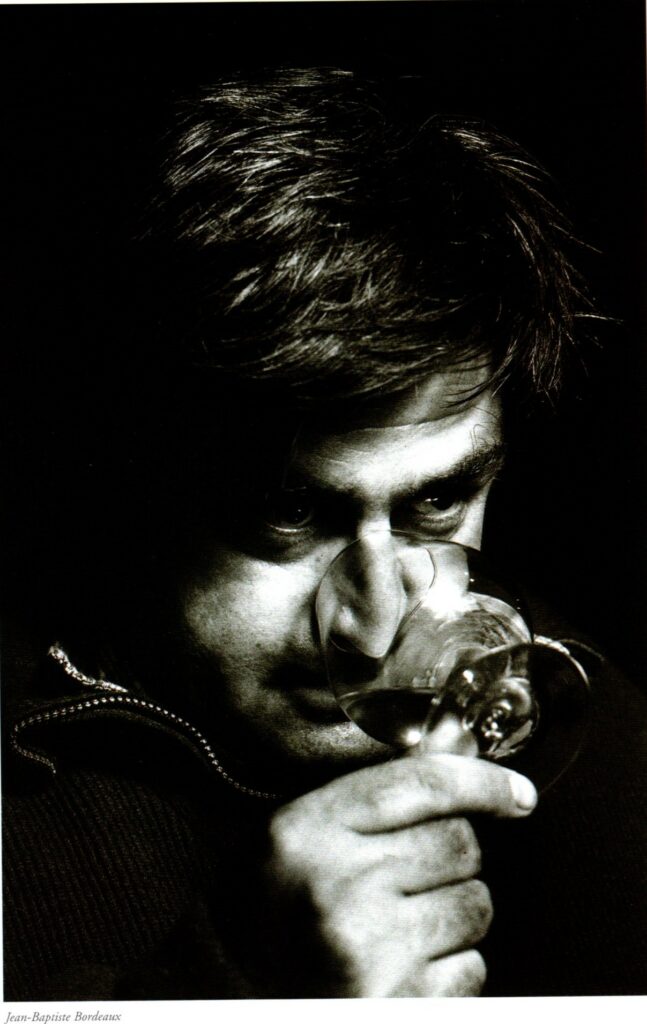

The Rousseau “Vidéo” barrels – extra‑tight‑grain French oak, air‑dried for 30–36 months and built for long ageing – framed the wine most harmoniously, amplifying depth and tension without shouting. Some casks destined for négociant Louis Jadot and for domaine‑bottler Étienne Sauzet, whose own teams specify the wood, felt more assertively marked by oak. That first tasting made clear why Jean‑Baptiste Bordeaux‑Montrieux – the quietly intense winemaker whose grandmother was a Thénard – had already begun reducing the share of Montrachet he sold to the grandes maisons to focus on his own bottlings.

When I returned in November 2025, that strategic shift was well advanced. I was delighted to be able to taste the 2024s, have a long conversation in the damp cellar with Jean‑Baptiste and his son André, and garner a sense of a domaine stepping, carefully, out of the shadows.

Science, Soil and a Short History Lesson

The Thénard story begins with chemistry. Louis‑Jacques Thénard, the son of a Burgundian ploughman, became a celebrated chemist, discovering hydrogen peroxide and cobalt blue, joining the Académie des Sciences and being ennobled as a Baron under Charles X. His reputation in fundamental chemistry anchored the Thénard name in French scientific life, while his descendants would root it more directly in the vineyards of Burgundy.

In 1842, his son Paul married Fanny Derrion‑Duplan, heiress to vineyards in Givry – the official birth of Domaine Baron Thénard – and it was Paul’s own work in agricultural chemistry, including carbon disulfide treatments that briefly checked phylloxera, which tied the family more closely to viticulture. A decade later they acquired the double‑vaulted cellar in Givry where the wines still age today, and in 1873 Paul bought two parcels of Montrachet on the Chassagne side, about 1.8 hectares in total, making the family the second‑largest owner of this grand cru, behind the Marquis de Laguiche.

The 20th century added Corton Clos du Roi Grand Cru, Pernand‑Vergelesses 1er Cru Île des Vergelesses, Grands‑Échezeaux Grand Cru and Chassagne‑Montrachet 1er Cru Clos Saint‑Jean, turning Thénard into a grand‑cru player whose heart remains in the Côte Chalonnaise. Today, the domaine farms roughly 20‑plus hectares, from Givry village to the hill of Corton and the slope of Montrachet, still in the hands of Paul and Fanny’s descendants.

The Bordeaux‑Montrieux Clan: A Hands-On Family Estate

Jean‑Baptiste grew up in Mercurey at the family’s other property, Domaine Bordeaux‑Montrieux, where his parents Jacques and Thérèse worked together. He studied agriculture in Lyon and Provence, then winemaking in Mâcon, and later ran Remoissenet Père et Fils in Beaune – valuable training for someone whose family’s Montrachet had long appeared under négociant labels.

Today, as head of Domaine Baron Thénard and its largest shareholder, he manages a compact team of 10–15 people with his wife Dominique and their son André. André oversees the vineyards and much of the cellar work; his sister Marie‑Aimée now runs Bordeaux‑Montrieux, where their beloved Mercurey Grand Clos Fortoul remains the family’s “death‑row wine” of choice. The domaine takes interns and seasonal workers from around the world, and they talk about building a “polyvalent” team – diverse in age, nationality and skills, but united in curiosity and care for the vines.

“My father gave me two educations,” André says. “First, he explained how precious our terroirs are – that we must fight for them, especially Montrachet, because we would never be able to get them back. Then he taught me that if you work very hard on your grapes, you can afford to be ‘lazy’ on your wines.” That philosophy is written into the wines: gentle extraction, long élevage and a style that is fine‑boned rather than flamboyant.

It is a resolutely personal operation. The cellar door is open six days a week; there is no online shop, no supermarket listing, and very little publicity. Half the production stays in France – largely in the east and in Paris, in restaurants, hotels, cavistes and direct sales – and half goes quietly to some 20‑plus export markets. Price points remain surprisingly sane for this level: Givry village around 25 euros, premiers crus at 30–40 euros, Corton and Clos Saint‑Jean near 90 euros, Grands‑Échezeaux around 300 euros and Montrachet Grand Cru roughly 900 euros, all with serious ageing curves.

Terroir in High Definition: From Givry to Montrachet Grand Cru

Givry – once the favourite red of Henri IV, who reportedly removed import duties to ensure its flow into Paris – is the cradle of the domaine. Its calcareous hillsides between 200 and 400 metres produce elegant, ageworthy Pinot Noir, and Thénard’s village Givry rouge, a blend of hillside and foot‑slope parcels, marries immediate charm with a 10‑year horizon.

The three Givry premiers crus show the estate’s terroir obsession at its best. Les Boischevaux, one of the estate’s emblematic sites and among the earliest‑recorded crus in Givry, sits on a steep mix of limestone and marl; low yields in hot years produce full‑bodied, structured wines with fine texture and 15‑year ageing potential. Clos du Cellier aux Moines, cultivated by Cistercian monks from the 12th century, faces due south on brown soils strewn with limestone pebbles and cooled by springs, giving fine, delicate reds and powerful yet elegant whites that age 15 years or more. Clos Saint‑Pierre, a monopole perched above Boischevaux on almost bare rock, with a spring and nearby woods preserving freshness, delivers more intense aromatics, tannic architecture and an 18‑year span – the “big brother” to the rest of the Givry range.

Beyond Givry, the lens tightens further. Pernand‑Vergelesses 1er Cru Île des Vergelesses, on well‑drained Ladoix limestone rich in fossil fragments, produces structured, complex wines that begin reserved but blossom with time. Chassagne‑Montrachet 1er Cru Clos Saint‑Jean, once used as a nursery for Givry replanting and only fully exploited since the 1960s, offers a remarkably consistent Chardonnay balancing freshness and aromatic intensity. Corton Clos du Roi Grand Cru, on iron‑rich brown soils over calcareous marl at around 300 metres, is the most refined of Corton’s climats – muscular yet poised, a 25‑year wine. Grands‑Échezeaux Grand Cru, on a gentle south‑east‑facing Bajocian limestone slab above Clos de Vougeot, gives some of Burgundy’s most complete Pinot: delicate, haunting and easily 25‑year-plus ageworthy material.

At the summit stands Montrachet Grand Cru. Thénard’s 1.8‑plus hectares, on the Chassagne side, sit on very shallow soils over hard limestone cut by a band of red marl, with a south to south‑east aspect that ensures even ripeness. The vines, replanted between the 1930s and 1970s, now average many decades of age and produce minuscule berries of startling aromatic density. In a typical year the domaine makes around 60‑plus hectolitres of Montrachet, and experience suggests you should give it at least 25 years in bottle to see it at its peak.

Gentle Hands, Long Maturation: How the Wines Are Made

Viticulture is quietly rigorous. The 20‑plus hectares, with an average vine age around 50 years, are planted at high density with carefully selected plant material, and yields are controlled via pruning, tillage and cover crops rather than aggressive green harvesting. Biodiversity – trees, woods, stone walls, meadows and fallow land – has always been protected around the plots, and in recent years insecticides and herbicides have been largely dropped in favour of cover crops, sheep in the vineyard and more thoughtful soil work. Pruning, increasingly inspired by Poussard on younger vines, is designed to preserve sap flow and vine health.

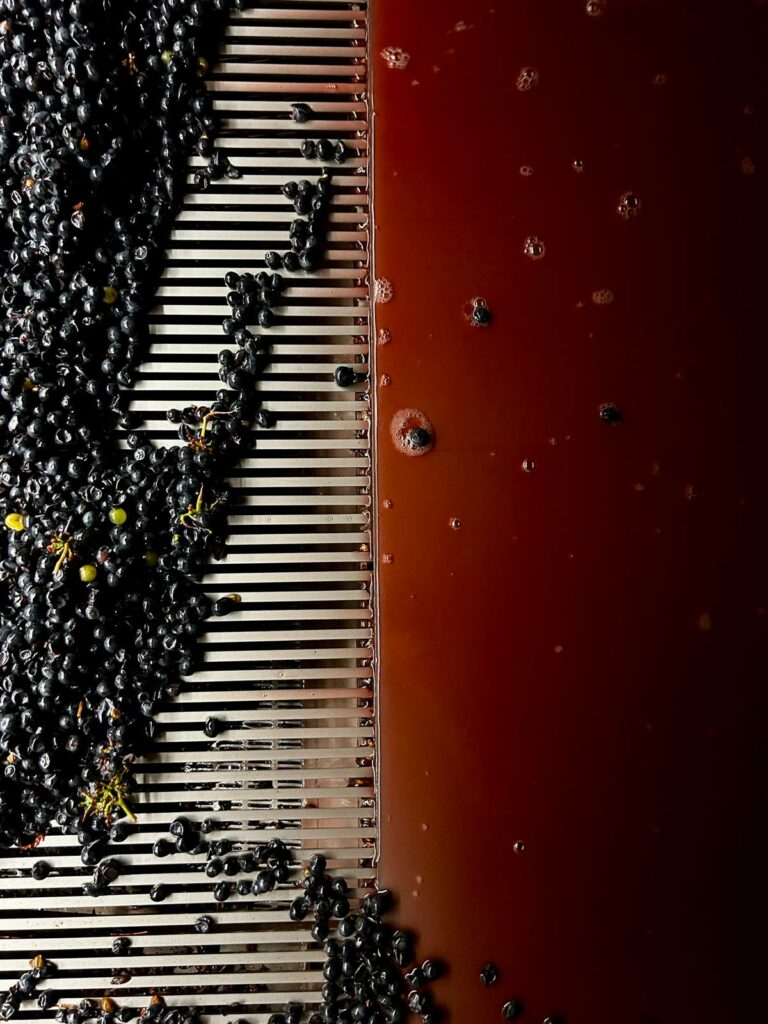

In the cellar, extraction is deliberately gentle. Grapes are sorted by hand. Reds are now fully destemmed after experiments with whole bunches proved ill‑suited to the domaine’s traditional two‑year barrel élevage, which left the wines too tight in bottle. Fermentations rely on indigenous yeasts, and great care is taken to select the right lees to nourish the wines, avoiding unnecessary additives.

The old Givry cellar, with its thick walls and rock‑cut floor, provides naturally cool, humid conditions that allow wines to age for up to two years without racking. Givry and the premiers crus spend their time in a mix of large foudres and classic 228‑litre barrels, with only about 5% new oak; Montrachet sees up to 50% new wood, always from several coopers, including the Rousseau “Vidéo” barrels that impressed so much in 2020. The aim is not to impose a “house oak” signature, but to use wood as a frame around the terroir, not a mask.

Tasting in the Steam: The 2024s from Barrel

In November 2025, tasting the 2024s from barrel in the damp cellar, my reading glasses fogging with steam, that philosophy was immediately clear. Givry 1er Cru Clos du Cellier aux Moines 2024 showed light, energetic plum fruit, a velvety mid‑palate and a sharp but pleasant finish, its tannins rounded by the south‑facing slope. Clos Saint‑Pierre 2024 was darker, more serious, with a rocky edge, sweet black‑fruit core and a firmer, more architectural frame that clearly marks it for the long haul.

Corton Clos du Roi Grand Cru 2024 was notably pretty and pure: the power of the terroir recast by a fresher vintage into floral aromas and juicy, tart red fruit, a wine that will drink well earlier than many Cortons without sacrificing depth. Grands‑Échezeaux Grand Cru 2024 was another step up in gravitas – darker in colour, plush and rich, with fine salinity and silky tannins; there is power behind the satin glove texture, and while it is already delicious from barrel, it clearly deserves more time.

The Montrachet quartet again provided the clearest lesson in oak and terroir. The four‑year‑old barrel showed almost no overt wood, just dense, coiled fruit and a long, saline finish. The two‑year‑old Rousseau cask added savoury and floral notes, grilled almond and a very clean, persistent line. The new Chassin barrel brought a touch more sweetness and vanilla, softening the edges but slightly blurring the focus. And the new Rousseau “Vidéo” barrel delivered the most complete picture – discreet but classy aromas, roasted lemon, hints of stone fruit and a racy, energetic finish where oak and terroir felt perfectly interlocked. As André put it best, “2024 offers a freshness across all the Montrachet barrels that beautifully balances the power of the site”.

Under the Radar by Design

Search for Domaine Baron Thénard online and you find terse merchant blurbs: founded in the 19th century, based in Givry, second‑largest owner of Montrachet, traditional wines, good value. Specialist forums note, almost in passing, that many collectors have drunk Thénard’s Montrachet for years under other people’s labels. Even within Burgundy, there are growers who know Montrachet, but could not place the cellar door.

Standing in that damp Givry cellar with André explaining why he prefers sheep to herbicides, it felt obvious that this is not an oversight but a choice. Thénard is a family domaine that happens to farm some of Burgundy’s greatest terroirs, not a luxury brand that happens to have a family attached to it. Its wines – from 25 euros Givry to 900 euros Montrachet Grand Cru – are built for the table and the cellar, not for trading algorithms.

For Burgundy lovers who value authenticity, patience and terroir over investment performance, that may be the most compelling reason of all to seek them out.

Lewis Chester DipWSET is a London-based wine & rare spirit collector and writer, member of the Académie du Champagne and Chevaliers du Tastevin, co-founder of Liquid Icons and the founder of the Golden Vines® Awards. He is also Honorary President and Head of Fundraising at the Gérard Basset Foundation, which funds diversity & inclusivity education programmes globally in the wine, spirits & hospitality sectors. The Golden Vines® 2026 will take place in London, UK between 6-8 November 2026, recognising the world’s best fine wine estates as voted by hundreds of fine wine professionals. Please register your interest for tickets on the website: liquidicons.com/work/golden-vines-awards.