To celebrate her 25th birthday in December, Natalie Belden decided a trip to Paris with her boyfriend was the only way to go. But after booking the voyage, the Washington, D.C.—based pharmaceutical sales representative happened to check tickets for the Venice Simplon-Orient-Express (VSOE)—a luxury train service on her travel bucket list. “Somehow there was an opening for the day after my birthday for two people,” she says. “It was a one-night from Vienna to Paris. We weren’t even planning on going to Vienna.” But she rearranged her itinerary anyway. “That’s how badly I needed to go on this trip. I have been wanting to go on this train for years and years and years.”

What’s so special about this particular locomotive? “It’s the lure of being in Europe and getting that old-timey feel,” Belden explains, “but also being on this luxurious train that is so glamorous, and you have cocktails and Champagne.” Even though the only lodging she was able to snag was a Historic Cabin, the VSOE’s smallest room category, the experience didn’t feel like settling.

“It literally looks like a movie, like you’re getting on a Disney ride,” she says—and everything from the service to the food left an impression. She recalls a waiter at lunch telling her, “Today we have scallops with truffle, but if you don’t want this, chef can prepare anything else for you.” Here at home, she adds with more than a modicum of understatement, “there’s nothing like that.”

To be sure, in the U.S., train travel is often the option of last resort. Most of us would rather drive or fly than trundle around in a quaint metal box that costs more and takes longer. In Europe, Asia, Africa, and Australia, however, a growing number of affluent American visitors are choosing rail for exactly those reasons: the slow pace, old-world ambience, and luxurious appointments that put it on a par with other elite experiences. In the world of ultra-luxury rail cruises, one night in a 100-year-old sleeper car can set you back more than $15,000—and, increasingly, the cars sell out months in advance.

Old-school train travel has no intention of trying to compete with the efficiency of jet-setting. Speed’s not the goal. Rather, the rail alternatives that have been springing up worldwide are focused on making five-star (stationary) hotel suites seem passé by one-upping them with ever-more lavish experiences. Leading the expansion in Europe are Belmond, the luxury travel operator owned by LVMH, and Accor, the French hotel group—both of which, confusingly, use the Orient Express brand name.

The nostalgia for the well-known route from Paris to Istanbul, immortalized by Agatha Christie’s 1934 bestseller Murder on the Orient Express, plays a major role in the brand’s extraordinary longevity. Christie was a frequent passenger, accompanying her archaeologist husband to Syria and Iraq, and today’s services attempt to re-create that golden age of travel, with more marquetry, lacquer, and crystal than one could ever hope to find on Amtrak or even on Europe’s no-frills state-run train network.

Simon Pielow, director of the Luxury Train Club, a U.K.-based travel agency, puts the surge in interest down to the slow-travel movement and the desire to find “convivial company, rediscover romance, and dress up,” noting, “we have never been busier.”

To meet demand, Belmond is adding new cabins to its VSOE train, which has dominated Europe’s luxury train market for 40 years. In 1982, James Sherwood, a shipping-container magnate and owner of the Hotel Cipriani in Venice, decided to resurrect the Orient Express to ferry customers from Paris to the Italian city. The original service had been established in 1883 by Georges Nagelmackers, a Belgian entrepreneur who brought the American Pullman–sleeping car concept to Europe. But it was disbanded in the 1970s, a victim of cheap air travel.

Sherwood “set about a spree of acquiring original carriages and restoring them,” says Gary Franklin, vice president of trains and cruises for VSOE. Today, those restored “wagon-lit” sleepers, the oldest of which dates from 1926, hold the train’s 72 Historic Cabins—the kind Belden counts herself as lucky to have booked—with seats that convert into bunks and shared bathrooms down the hall. Prices start from about $4,100 per person per night. Between 2018 and 2021, some original cars were converted into six luxury en suite cabins known as Grand Suites, in which a one-night trip costs upwards of $12,200 per person. In June, a new intermediate suite category will launch, starting at about $8,072 a head. Most routes are one-nighters linking an ever-expanding list of European cities, with a few longer loops starting and ending in Paris. To preserve its rarity and mystique, VSOE runs the namesake Paris-to-Istanbul journey just once a year.

A commitment to decorative panache seems to be an important part of the appeal. “I’m probably biased,” says Franklin, “but I think [the VSOE trains] are like works of art.” The new suites will feature marble en suite bathrooms and a lounge that transforms into double or twin beds. The Art Deco ornamentation is nature-themed with, for example, “vivid velvet greens and intricate flower marquetry” in the La Campagne (countryside) Cabin.

The Grand Suites, each of which is themed around a European capital, come with underfloor heating, private dining, free-flowing Champagne, caviar on arrival, and chauffeured transfers to and from the train. Artisans from Parisian ateliers have designed every detail, from mosaics to lacquered furniture to Lalique glass. Belmond intends to add more Grand Suites in the coming years.

But looks aren’t this train’s only strong suit: The VSOE’s staff puts as high a premium on service as its designers do on interiors. “The legend is that the bar will never close while there’s a customer in there,” says Franklin. “People who are looking to celebrate will find a lot of kindred spirits on board the train.”

That’s what Natalie Belden found during her trip. “As you get on, you no longer have to worry about anything: Your bags are already being brought to your cabin; a glass of Champagne is given to you; you meet your butler, who is on call for you every second,” she recalls. “So immediately I was like, ‘Well, this is amazing.’ ”

And the novelty of the experience (plus the tight quarters) means there’s nowhere to hide lapsed efforts. Not that Belden noticed any.

“I think that flying first class or by private jet is so routine now that the details are sometimes overlooked,” she says. “And there was not a single detail that was overlooked in this experience.

– Natalie Belden

The appetite for luxury trains is such that the VSOE is getting a rival. The right to operate a train under the name Venice Simplon-Orient-Express (the name comes from the Simplon Tunnel, which connects Brig, Switzerland, to Domodossola, Italy, via a shortcut under the Simplon Pass, though today the VSOE takes a different route through the Alps) is licensed to Belmond from SNCF, the French national railway operator, which inherited the remnants of the original service. After first partnering with SNCF in 2017 to develop the Orient Express brand, Accor now controls the name.

Accor intends to apply the brand name to a wide range of luxury travel experiences, including hotels and a sailing yacht as well as two Orient Express trains, which, like the VSOE, are made up of refurbished vintage rail cars. The first, an Italian service called Orient Express La Dolce Vita, will launch in 2024, composed of 1970s cars. The second, simply called the Orient Express, will launch in 2025, running on a slightly different route between Paris and Istanbul than the VSOE. Accor’s new Orient Express will travel via Munich and Vienna, stopping daily “to experience amazing wineries, castles, and so on,” says Guillaume de Saint Lager, vice president of Accor’s Orient Express. By contrast, the VSOE stops in Bucharest and Budapest, where guests stay overnight in five-star hotels.

Accor will follow suit once it begins opening Orient Express hotels in the cities served by its trains, taking the example of Sherwood and Nagelmackers, who, says de Saint Lager, “created the first international [hotel] chain from Paris to Beijing,” with the aim of “driving, defining, crafting the experience of your guests, making sure that they will buy tickets from you, travel with you, stay in your hotels. And that’s exactly what we are doing today.” The Orient Express La Minerva hotel will open in Rome next year, and the Orient Express Palazzo Donà Giovannelli in Venice will follow soon after.

Pre-reservations for La Dolce Vita have already opened for journeys connecting Rome with either Venice, Tuscany, or Sicily, at prices starting from about $2,200 per person per night. The cars have been refurbished by design house Dimorestudio to reflect midcentury Italian style—and are straight out of a Mad Men set, with furnishings that nod to the period, brass detailing, and walls of smoked mirror.

The Orient Express will consist of 17 cars from a 1920s and ’30s set Accor acquired after a researcher tracked them down at the Polish-Belarusian border in 2015. French architect Maxime d’Angeac is overseeing the design, taking a more contemporary approach than VSOE. For example, guests can watch chefs at work through a glass wall separating the kitchen from the dining car, which has a mirrored ceiling and shimmering bronze wall panels. In the vaulted-ceiling bar car, emerald velvet Art Deco banquettes are arranged in little nooks around circular tables, each of which will have a call button for Champagne and a clock that chimes at the dinner hour.

The suites are arrayed in velvet, leather, and glossy mahogany paneling, with curvaceous lines and moody lighting. Headboards feature mother-of-pearl and bronze beading. Several original Lalique merles et raisins (blackbirds and grapes) panels survive. All cabins have been remodeled to include en suite bathrooms, and the living room–like areas are reconfigured at night to transform into sleeping spaces. The effect, as with the VSOE, is reminiscent of an ingenious marquetry desk or gaming table, full of unfolding sections and hidden drawers.

Accor’s Orient Express will also host a single Presidential Suite, accessed by its own private entrance and decorated with Macassar ebony and rosewood columns, with two velvet-walled bedrooms, a living room and dining area, a gas fireplace, and a bathroom with a tub.

De Saint Lager expects demand to come principally from the U.S. and the U.K., “because American and English people are just mad about trains.” But the appetite for luxury train travel exists the world over, from the Maharajas’ Express, which tours the historic cities of Northern India, to Australia’s the Ghan, which journeys between Adelaide and Darwin through a desert landscape. Belmond has a portfolio of six trains, including two in Peru and one exploring Southeast Asia, though none matches the VSOE for luxury. Pielow, of the Luxury Train Club, recommends Rovos Rail, in South Africa, and Japan’s Seven Stars in Kyushu, though demand for the latter is so high that tickets are allocated by lottery and are “extra-super-difficult” to acquire.

One to watch, he adds, is Le Grand Tour, which will start traversing France’s wine regions this autumn. Created by Puy du Fou, which operates historical theme parks, the service will run two-day trips from Paris to Reims and Beaune, as well as a six-day loop through Provence, Saint-Émilion, and the Loire Valley, stopping to visit châteaux en route. Prices for the 18 en suite cabins range from about $3,050 to $10,890 per person per night.

On board, the experience will focus on the French art de vivre and gastronomy, according to a Puy du Fou spokesperson, with menus designed by three-Michelin-starred chef Alexandre Couillon. The cars, which date from the 1960s, have been decorated in Belle Epoque style, with swaths of fringed velvet drapery, lacy tablecloths, and gold braid.

The same pastiche 19th-century aesthetic prevails at Golden Eagle Luxury Trains, a 30-year-old former Russia specialist that has pivoted to European and Central Asian tours and is enjoying a spike in popularity. Bookings on its Danube Express—which explores some of Eastern Europe’s more remote corners, including a Castles of Transylvania tour—have increased by more than 20 percent in the past year, with passengers coming predominantly from the U.S., according to Joely Garland, the company’s marketing manager. Suites are “nostalgic,” she says. Chic is not the point. The idea is that “when you step on the train, you have gone to another world and a different time.”

If the decor is conservative, the destinations are decidedly adventurous, especially the 16-day Caspian Odyssey from Armenia to Kazakhstan. It’s the most expensive trip in Golden Eagle’s Silk Road collection, at $56,895 per person for an Imperial Suite. Highlights include visits to the Armenian monastery of Geghard, a private performance of Georgian polyphonic singing in the ancient cave city of Uplistsikhe, night viewing of the Darvaza burning gas crater in Turkmenistan’s Karakum desert, and tours of the historical Uzbek cities of Khiva, Bukhara, and Samarkand.

Across the board, the growth trend is for the most elevated, expensive experiences. In May 2024, Belmond will add a new Grand Suite category to its Royal Scotsman service, with prices ranging from $3,210 to $5,125 per person per night. The train, which tours the Scottish Highlands, boasts a spa car and an open-air observation area, the only one of its kind in Europe. Trips include visits to remote castles, Jacobite monuments, whisky distilleries, mountains, lochs, white-sand beaches, and royal stately homes. Interest is so high that this year’s tickets nearly sold out by the end of March, says Franklin.

The Royal Scotsman’s Grand Suites were created by Tristan Auer, a Parisian designer who works with Mandarin Oriental, Four Seasons, and Rosewood hotels when he’s not customizing jets, cars, or boats for private clients. For this, his first train project, he collaborated with Scottish craftsmen to design the furnishings, including a Scottish-larch dining table with pewter detailing and fabrics including cashmere and tweeds. For tartans, he worked with Araminta Campbell, the Edinburgh-based textile weavers, to create bespoke patterns: “They do it like the old days, and they’re passionate,” Auer says.

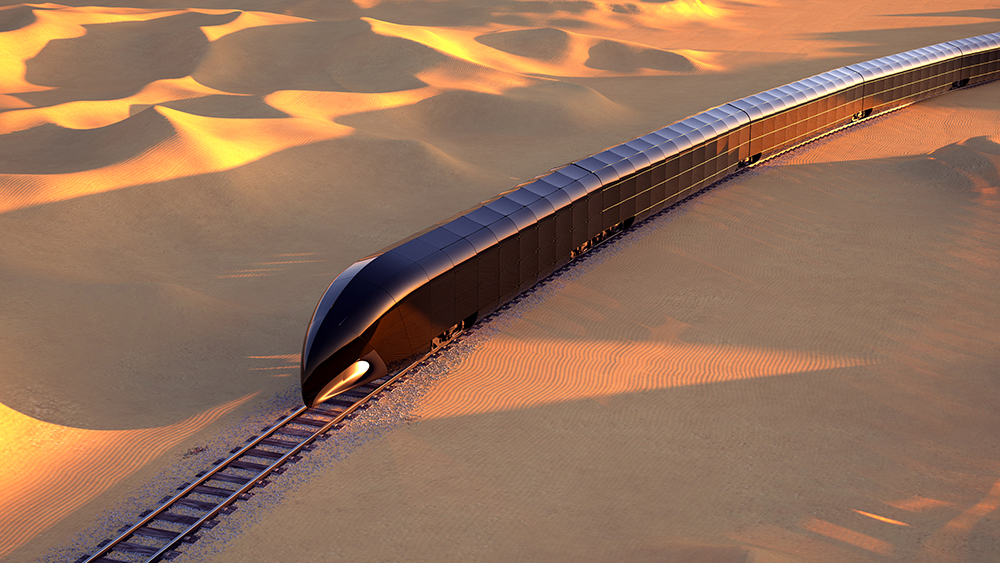

The only luxury train that does not lean heavily into the heritage theme is still in the concept phase. In 2021, French superyacht designer Thierry Gaugain launched his blueprint for the ultra-modern G-Train, a 14-car palace on rails intended as a private plaything for one wealthy owner. While he waits for the right customer, Gaugain is recruiting a construction team, including a collaboration with Saint-Gobain, a 350-year-old French glassmaking firm whose previous work includes the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles and which now makes glass for spaceships.

The G-Train—with its black, snakelike appearance, digital controls, internal gardens, open-air sections, sophisticated sound and lighting effects, and glass walls that can switch from opaque to transparent—fills a gap in the market for a train that showcases cutting-edge technology rather than replicating the past.

For now, though, the railway vogue is for nostalgia, as the multiple remakes of Murder on the Orient Express can attest to. Languorous voyages to the wilder corners of Europe have an analog and restorative appeal in an age of information overload and fractured attention spans.

In his design for the Royal Scotsman, Auer says he aimed to create “a time capsule,” not only in the aesthetic sense but also behaviorally. “We thought about trying to push people not to look at their iPhones when traveling on this train,” he explains.

“To slow down. Everything is going faster and faster, and luxury now is having time and using it for the right purpose.”

This gift of pure relaxation was what appealed most strongly to Natalie Belden during her night on the VSOE. “It felt so exclusive, so different from how things work in our lives now. I don’t think I looked at my phone once for six hours,” she says of the time she spent socializing in the bar car. “You’re transported to a different world, and you’re not concerned about anything that’s happening outside of this train. You just feel like you’re traveling through time.”